Four

The winter, cold and bitter, passed once again, just as it always had. Snow covered the ground around Tom’s home, providing a place to hide. Safe. Silent. After a brief period of mourning, his meetings with the literary elite resumed, taking on more life as they began to consider what kind of death soliloquy William Shakespeare would have written for Franz Kafka’s cockroach. And Tom had begun to prepare a full series of paintings for a new edition of Jane Eyre. Indeed, Tom was almost happy—almost.

One day, as he was grinding the last store of winter wheat into flour when there came a knock at the door. Tom started, then turned his head to stare darkly at whoever stood behind it. “No one’s knocked on that door in years,” he whispered. Tom grunted and considered simply hiding out just as he had done in the early years when religious evangelists and sales people could still find the road. He would let them knock until the futility of their effort sent them back out on their way. Distantly, however, still rattling somewhere down deep in the chasm of his brokenness, there was a boy who remembered the joy of visitors—real visitors. Despite himself, he wanted to see who was on the other side of that door.

Source

Source

Slowly, Tom approached the door and opened it. Outside in the afternoon sun, fidgeting and biting her lip, stood the woman who had appeared in his living room months before. Tom took in a sharp breath and froze. His eyes narrowed, “Go away! I’m not going to talk to a figment of my own damned imagination.” An image of himself deeply engrossed in conversation with a bunch of paintings flashed before his mind, and he groaned. “That’s different,” he insisted in a sharp and silent voice. “I know I’m talking to myself there.”

He frowned bitterly and spoke again, “Look, I don’t know who you are or what you are, but you don’t belong here. I don’t want any visitors—imaginary or otherwise. Go away.” With that, he closed the door and stalked back to the kitchen.

Three more knocks came in rapid succession. “But I need to talk to you.” Her voice was clear and light and pure—like the sound of a flute. “I…” she paused, “I want to talk to you.”

Tom put his hand on a chair to stop his trembling and closed his eyes, breathing deeply through his nose. In his mind’s eye, he could see the lone cottonwood tree standing on a hill. He stared at it, sighed, and thought to himself, “I guess if I’m going to lose my mind, I may as well embrace it. Besides,” echoed the boy deep within, “it will be nice to talk to someone who actually talks back—even if it’s a figment of my own imagination come to life.”

Source

Tom cracked the door and looked at the young woman. She was perhaps twenty-two and clearly uncomfortable. There was a gentle sparkle to her emerald-green eyes, though they opened wide with restrained fear at the sight of him. Recovering, she flashed an awkward, dimpled smile and laughed uncomfortably, making a sound like the soft ring of silver bells, “Um…Hello.”

“Who are you?” Tom asked, his voice sounding more gruff than he had expected.

“My name is Lynn. Lynn Halver.” They stood in silence for a few moments, Tom scrutinizing her with narrowed eyes while she unconsciously raised a hand to her hidden necklace. She seemed to struggle with figuring out what to say next. “My mother’s family used to live on this farm. A long, long time ago.”

Tom grunted, “Must have been a hell of a long time ago.”

“Well,” Lynn looked uncomfortable, “yes.”

“So, what do you want from me? Why are you here?”

“My mother asked me to come back here because she…can’t. I’m here because I’m confused. There are so many things I don’t understand, and I want to.”

“What is it you don’t understand?” asked Tom.

“I don’t understand why my mother sent me here—what I’m supposed to learn by being here.” Lynn now looked genuinely confused and almost scared that he might slam the door in her face. Though he was trying hard, Tom could not remain bitter at such an open, honest, and youthful vulnerability. Finally, he opened the door.

Tom became suddenly conscious of his worn and faded clothes—simple khaki work pants and a light grey shirt that had faded to white. The drabness of his clothes was exaggerated as he stood beside her. She wore a light pink blouse—probably made of silk, by the look of it—a longish tan skirt with some matching lace around the edges, and small black shoes. “So…” Tom shifted uncomfortably, “you want to sit down?”

Lynn smiled briefly, “Thank you.” Tom caught himself smiling back and rushed to cover it with a grimmace. They crossed into the living room where Lynn drifted to the couch and sat lightly beside the coffee table she had knocked over several months before. Watching her there, sitting on the faded couch, Tom marveled at how strange it was to have this young girl here in his house, like a bright carnation popping up in the frozen tundra.

Tom looked at her with guarded curiosity. Lynn kept looked around the room examining things as if in disbelief that what she saw was real. Though she did this for some time, it was still she who spoke first, “I’m sorry. This place is so different from…where I come from. May I ask your name?”

“My name’s Tom,” said Tom, flatly.

“Oh. It’s nice to meet you, Tom,” she responded, her dimpled smile returning.

“Likewise.”

Lynn looked at Tom for a little while, fumbling absentmindedly with her necklace, still hidden beneath her blouse. Her staring made him feel awkward, so he turned his attention to the window.

Finally, Tom said, “Can I ask you a question?” Shifting his eyes to look at her, Tom found her sitting quietly and listening attentively. “Why did you knock on my door? Last time you just popped into my living room.”

Lynn looked at the floor briefly and then returned her eyes to him, “I’m afraid I just don’t know. I guess I was thinking that it would be more polite to knock. I didn’t want you to think that I was here to…” she paused, “…invade your space.”

“Invading my space?” whispered Tom. “Now a figment of my own imagination is worried about invading my space? Yep,” he concluded, “Crazy.” He spoke, “Well, that’s a good thing. I’m a very private person.”

“You have a very nice little farm here,” said Lynn. “Could I see the house?” Tom’s eyes, which had begun to relax just a bit, closed like an iron gate.

“No. No tours.” No one came into the dark corners of this house. There was too much of himself hidden there. “You want to talk? Let’s talk.”

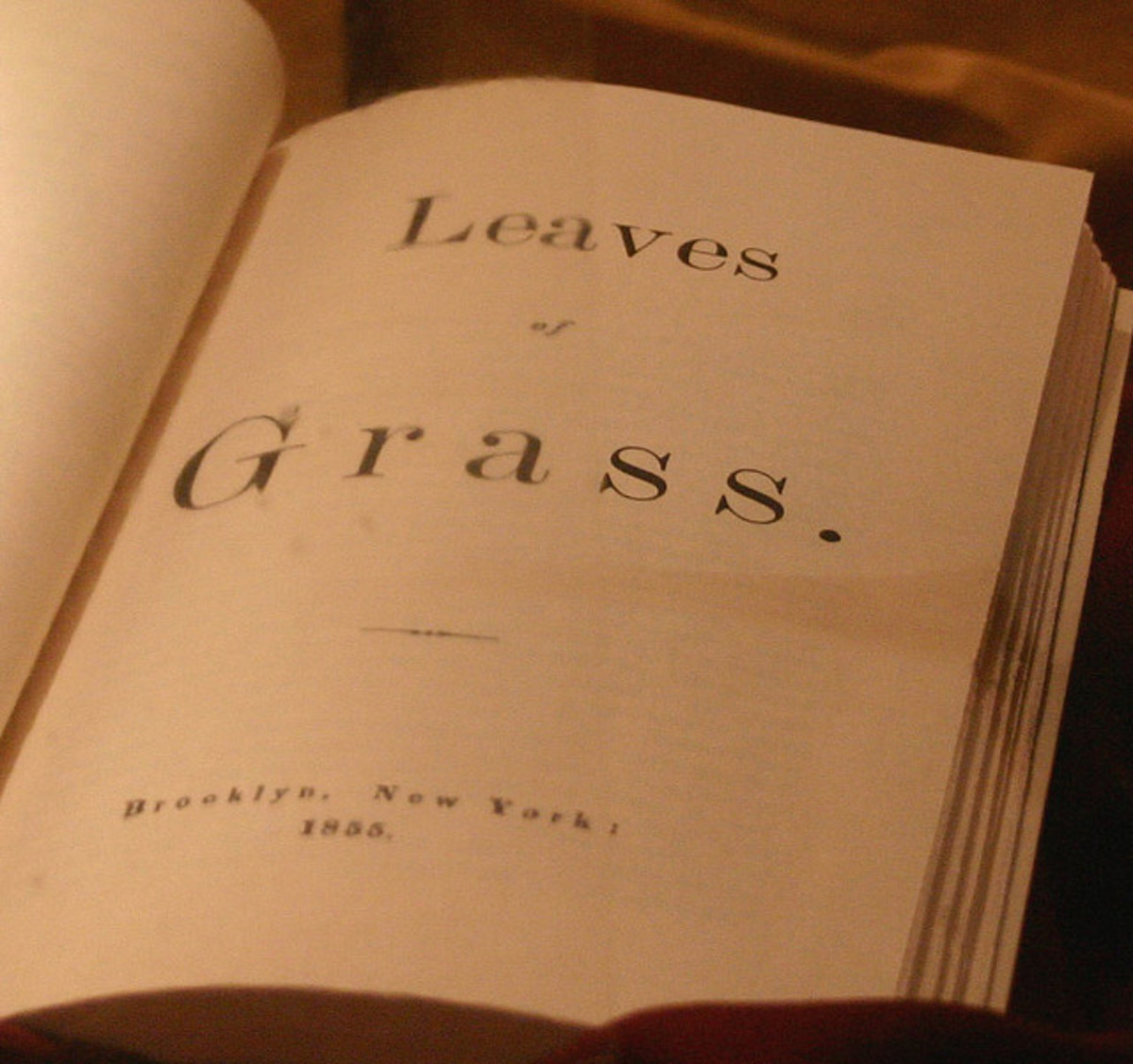

Lynn, looking startled again, backed off immediately. “Oh. I’m sorry. That’s no problem.” Lynn glanced around the room trying to grasp at something to say, “I noticed,” she cleared her throat, “the last time I was here that you have a lot of books—and they are in exceptional condition given how old they are.”

Source

“Thank you,” said Tom. “Do you read?” With these words, the light of curiosity in his eyes returned. “Say, have you ever read A Midsummer Night’s Dream?”

Lynn smiled, openly this time, “I love Shakespeare.”

“Yes. William is…ahem…I mean Shakespeare is wonderful.”

There was still a lump in Tom’s stomach, but it had been such a long time since he had had someone to talk to—especially someone as engaging as Lynn—that he found it difficult to maintain his guarded distance. He quickly discovered that, through the influence of her mother, she was quite well read. She had read many of the books on Tom’s bookshelf, and he soon found out that, more than just reading them, she had thoughtfully considered many of them.

Finally: someone to talk to who actually talked back! If it was his own imagination, he was getting good at fooling himself because she even held opposing opinions that he did not have to work out ahead of time. They quickly fell into a discussion of Tom’s books that lasted several hours.

Occasionally, Lynn tried to veer towards other, more personal, subjects, but Tom immediately shut down, so she would, in her soft and quiet way, coax him back into conversation with another literary observation or question.

***

As the afternoon sun began to wane, Lynn finally rose to leave, and Tom was surprised to find that he didn’t want her to go. “Well, would you like to come back?”

“I would love to,” came Lynn’s reply.

Tom smiled broadly, and then walked her to the door. He let her out, and was momentarily surprised when she shimmered into nothingness as she stepped off the porch.

Five

Lynn returned each afternoon for nearly a week, always appearing on the porch and then knocking at the door. Tom took to standing at the kitchen window to wait for her to appear, trying to be sure that what he was seeing was real. Every day, Lynn materialized out of thin air and knocked.

Their conversation continued to run largely around the literature that Tom so loved, but he soon brought down his paintings from the attic to share with her as well. Of course, he was careful not mention how much conversation he had shared with the portraits, and he still refused to allow her to see his painting studio upstairs; there was simply too much of himself on display there. Still, she enjoyed seeing his work, and on one occasion, he did take her to the back to see his small garden. He spoke very briefly of his long history on the farm and was very careful to keep charge of her attention the entire time they were outside of the house.

Source

Lynn always seemed to enjoyed herself, though she did seem distant to Tom every now and then, as if she were trying to see something a long way away or trying to resolve some riddle playing in the back of her mind. On one of these occasions, Tom had interrupted her and asked why a ghost would ever expect to get something from him that would help her find peace. She had looked at him strangely, then, and said, “A ghost? But… Well… I’m still not sure why I’m here, Tom. I’ll know it when I see it.”

On the fifth day, late in the afternoon, Lynn asked him to sit with her at the kitchen table. They sat in the warm sunlight that shone through the window—Tom made sure to open it now in the afternoons. Lynn sat, absentmindedly toying with the necklace beneath her blouse once again, a habit Tom had begun to notice. For a time, sitting there at the table, Lynn gazed at him with a peculiar expression on her face. It began to make him nervous. She looked at him as if she were trying to convince herself of something. “I have a question.”

“Yes?” he replied, unsure.

“So, you have lived here in this house all alone for the past forty years?”

“Yes. That’s been my choice.” Tom’s eyes narrowed ever so slightly.

“And you have not had any contact with the outside world? You’ve never even been off the farm?”

“No. We’ve talked about this before, you know. Soon after finding myself…” he paused to find the right words to put in here, “…in charge of the place, I gave up on most of the acreage—didn’t need it for myself. I planted a small garden just behind the house and kept a few chickens and cows. Eggs, milk, meat, and vegetables; food from my work, water from the well, and a roof over my head. What else does a person need?”

Source

“How about paints? You have some wonderful paintings, Tom, but you can’t have painted everything up in the loft without a good supply of materials.”

“Yeah, I had that problem. I had a few paints to start with. A few canvases, too. They belonged to…” Tom looked at Lynn and considered something, but changed his mind. “Well anyway, once I used them up, I found I had enjoyed it so much I thought about going to get more. Decided against it. Hell, I had nothing but time on my hands that winter, so I started mixing my own paints and building canvases. First attempts were a real mess. As I said, though, I had lots of time. Actually took about three years to get something genuinely usable, but I got there eventually.”

“You are certainly persistent. What about your garden tools? Have you ever had to replace them?”

“They’re good tools, and I take care of them,” he responded simply.

“So, in forty years,” Lynn took time to emphasize these words, “in forty yearsyou’ve never had to replace them? Those are some exceptionally good tools.”

He paused. His look of mild irritation froze for a moment, then, like a strong wind that suddenly shifts directions, became a look of confusion. He pulled his hand up to his face and scratched his chin. Sat back. Rubbed his nose. Shifted uncomfortably in his chair.

She’d been visiting for nearly a week and had managed to keep her nose out of his business almost entirely. So much for that. Tom’s face froze as hard as the snow-covered ground outside. “Look, do you have a point? I’m not interested in discussing this anymore.”

Lynn’s eyes began to take on a look of focused purpose. “What about your studio, Tom? Why won’t you ever let me see it?”

“Why?” Tom found he was yelling now. “Have you been snooping around? What have you seen?”

“Tom, I didn’t need to see anything to know that you’re holding something back. You know, you’re a lot like my son: he can keep a secret, but he can’t hide the fact that he’s doing it. Neither can you.”

At this, Tom stood up, “You haven’t seen my studio because I didn’t want you to see it! We’re done here. Get out.”

Lynn struggled to remain calm, “Something’s been on your mind, Tom. You’re friendly but distant. You have to understand that I’m trying to help you—to help both of us. If you would just…”

Tom slammed his hand down on the table. “Get out. This is my house, and you are not welcome here anymore. Get out!” Tom roared. Lynn looked back at him with tears of defiance threatening to well over in her eyes. She stood, turned sharply, stalked over to the door, and left without a word.

Tom slammed the door closed behind her and bowed his head in exhausted frustration. He’d messed it up; he was mad, but he hadn’t wanted her to leave. Not really. He didn’t want to think about what that might mean, however, so he decided to be angry instead. After all, he had spent a lifetime learning to ignore what he really felt.

Six

Two days later, it happened: Lynn knocked again. Tom had barricaded himself in his painting studio in the attic. The literary masters were now stacked in a dusty corner. On the table lay canvases of various sizes scarred with dark, agitated images in black and red: the ruins of a building, the black smear of a shadow with menacing eyes, and a gentle face consumed in flames. Sweat was thick on Tom’s brow as he violently thrust his visions down on the canvas.

Lynn stood on the porch for about thirty minutes before going away, knocking repeatedly. Again, and again, and again, she returned to the door of the house where Tom, like a cornered animal, cowered inside. Finally, a day came when she did not return. This confused Tom and he found it very difficult to work out exactly how he should feel about it.

Source

Two days later, it happened: Lynn knocked again. Tom had barricaded himself in his painting studio in the attic. The literary masters were now stacked in a dusty corner. On the table lay canvases of various sizes scarred with dark, agitated images in black and red: the ruins of a building, the black smear of a shadow with menacing eyes, and a gentle face consumed in flames. Sweat was thick on Tom’s brow as he violently thrust his visions down on the canvas.

Lynn stood on the porch for about thirty minutes before going away, knocking repeatedly. Again, and again, and again, she returned to the door of the house where Tom, like a cornered animal, cowered inside. Finally, a day came when she did not return. This confused Tom and he found it very difficult to work out exactly how he should feel about it.

Source

A few days after Lynn’s final appearance, Tom came down from the attic completely absorbed in the final pages of Leaves of Grass. He had almost passed the sofa when he started, tripped, and fell in a heap on the floor. There, on his sofa, quiet and unabashed, sat Lynn. She look at him with grim determination. Rushing to stand, angry words flashed behind Tom’s eyes, but he did not get the chance to speak them.

“Tom,” Lynn’s voice was firm, commanding, and gentle, “I know that you don’t want to talk to me. I’m sorry for this breach of courtesy, but you have to believe that I don’t want to be a nuisance to you. I’m sorry, Tom, but, frankly, this is what you need, so here I am.”

“I told you I’ve had enough! I don’t want to talk to you anymore.” Tom scowled at her as he moved to his chair, “What happened to ‘I don’t want to invade your space?’ You were knocking at the door, but now you’re sitting,” he paused to emphasize the next word, “uninvited, on my couch.”

Lynn was clearly straining to remain calm, “Tom, I have come to care enough about you to help you despite your own resistance. I’m not leaving.”

Source

Tom glared at her with disgust, clenching his jaw and grinding his teeth. He looked down at the floor and closed his eyes. The shadows were closing in from all sides now, and this upstart young woman was pushing him into them—forcing him to tear the skin away and reveal the ugliness that lay on the underside of memory. He had become too accustomed to the safety of his spiritual atrophy. “Dear God,” he thought, “to move again. It’s too much. No. I won’t do it.”

She took his trembling hand into her own firm grip. She pressed it for a moment, and then looked squarely into his deep, aged eyes. “I am here; I will be with you. Tom, I need you to tell me. I need you to tell me what you’ve been hiding.”

“I…” Tom tried to return her gaze, but his eyes closed and dropped away to stare into his own lonely darkness. “I don’t think I can, Lynn. There is a part of me that wants to tell you, but it’s too much. Forty years is just too much.”

Lynn reached over and lifted his chin so that his eyes looked into hers. She smiled, “You have nothing to fear. We will walk through this together.”

It was time.

Seven

“I was nine,” said Tom quietly, looking down at the floor between his hands. “It was a few days before the Fourth of July, and I’d been given strict instructions from Mom to leave the fireworks alone until then. But we had smoke bombs. I loved smoke bombs. Never was much for listening, neither, so I sneaked some smoke bombs into the barn.” Tom looked at Lynn dryly, “Yeah. I know. The barn.”

They sat together in silence for several minutes. As the time passed, his face transformed. No eyes carved from cold stone had ever been harder than his as he stared off at an infinitely distant horizon; he looked as if he no longer wished to be cursed with sight. Finally, his voice came hesitantly, “As I entered the barn, I noticed all the animals were out to pasture, so I could light some smoke bombs and watch them burn their orange and green haze into the air.

“On the fourth one, however, I was startled by…a sound,” here he paused. It took several moments before he was able to choke out the rest of the words, “…my…sister’s voice, ‘I’m gonna tell Mom! You’re not supposed to be touching those, and you know it!’ I didn’t know she was there. She scared me.” As he said these words, he sat looking at his hand which he held as if it were holding something between its index finger and thumb. Moving like there were some kind of dark magic about the act, Tom released the invisible object he had been holding and watched it fall. “I dropped the match.” Slowly, his hand closed into a fist, and his eyes shut tight.

Source

Source

Once again, silence surrounded them, thick and heavy.

When he opened his eyes, Lynn could see the fire raging behind them. “It burned. Furious. Fast. Unforgiving. June was hiding up in the loft. I yelled at her to get down, but she was afraid. I looked for a way to get to her, but the fire had caught on the hay and blocked my way up. I yelled at her to climb down—screamed at her. Finally, she started to climb down. Her nerves got the best of her though, and, half-way down, she slipped and fell.” He stretched out his arms as if trying to reach into the past and catch her. He held his arms outstretched for a moment, his fingers closed slowly, and his arms dropped. “She hit the ground. She never moved again.”

“I kept trying to get to her for such a long time that I let the fire close in behind me. The last thing I remember is the sound of my parents’ voices calling out in fear and the sound of a support beam cracking over my head. After that, there’s only darkness.” Slowly, Tom turned his eyes to look at Lynn for the first time since he had begun his confession.

The crack that had formed in the wall of his spirit, covered over by the scabs of many years, began to bleed, sharp and painful. “I woke up three days later in my bed. I had a horrible headache and a huge lump on top of my head. I called out for my parents, for my sister, for anyone, but no one answered. I searched for my family everywhere. Everyone was gone,” his eyes closed. “Everyone was gone.”

“I didn’t understand at first, but then I went outside and saw it. There,” Tom lifted his hand and pointed towards the west wall of the house. He turned his eyes to stare at the cottonwood tree that stood on a hill beyond the walls. “There, I saw, silhouetted by the setting sun, our favorite cottonwood tree with a wooden cross standing below it. Before the cross, a mound of earth. At that moment, standing in the long shadow of the cottonwood tree, I knew what had happened—I knew that my sister, June, was buried there. My parents must have buried her there. Unable to bear seeing me—or even speaking to me—they went away. I was alone. Been alone ever since.”

Source

Tom turned his eyes, huge and glistening, back to Lynn. She returned his gaze, quiet tears falling freely from her eyes. She smiled in reassurance and took his hand. “Thank you,” he said. They sat still for a moment. Eventually, Tom stood and sat down on the floor beside Lynn. He looked up at her, his breathing shallow, and laid his head on her soft lap. Taking in a deep breath, he released it and cried.

Time bled slowly away as the minutes passed.

Finally, Lynn smiled down at him and asked, “Will you take a walk with me, Tom?” Determination was set in his eyes, despite the shadow of fear that lived within them. They stood. It was a long time before they moved. She looked at him, at his tormented face, and took his hand; the gentle firmness of her delicate grip gave him strength, and, finally, he stepped forward.

Lynn led him out the door, and they turned to the west—towards the hill that lay past the ruin of the barn, towards the old cottonwood tree, to the hill of the grave. Reluctantly, Tom moved forward. He had never been there. In almost forty years, Tom had never approached the grave of his sister. He could not bear it alone. But today he was not alone.

Source

They came under the shadow of the tree, whose leaves were just now budding in the warm first breath of spring. As Tom approached the shadow, he hesitated for a moment, and then stepped into its darkness. They stopped at the small mound of earth, marked by the roughly-carved cross, where the grass was just now beginning to green. Tom stood looking down as the breeze caressed his tear-worn face. He fell to his knees, touched the earth lightly with his hand, and whispered, “Forgive me.”

Lynn put her hand lightly on Tom’s shoulder. “You’ve never been to this grave before, have you Tom?”

“No.”

“I know. I’ve known it for some time now. You couldn’t have.” Tom looked up at her, puzzled.

“How could you know that? How could you have discovered any of this? How could you have known about the weight that I carry?”

“Guilt.” said Lynn dryly. She pressed her lips together in a brief smile of sympathy, “Guilt blinds us, Tom, and it is so often misplaced. My own mother was plagued by it. I finally understand. Unable to come to terms with her own guilt, she carried it like stones on her heart.” Lynn laughed sadly. “Really, she was very much like you, Tom.” Lynn’s eyes became distant, “You see, she never clearly explained why she wanted me to come here. She told me where to find it and made it clear that I would find answers here in the ruins of this farmland, but that was all. She died, before she had the strength to come back here herself. Before she had the strength to tell me her story. She died too young—just a year ago, in fact.”

“But, just a year ago? How? You said your family lived here a long time ago—it had to have been over fifty years ago! And besides, you’re a…ghost.”

“No,” replied Lynn. “You’re confused, Tom. My mother’s family did live here: my mother, her mother, her father, and the secret she never revealed to me. They all lived here.”

Tom looked desperately confused.

“Look at the cross, Tom.”

He turned his eyes to look at the cross, and there, carved in simple letters that he recognized as the work of his father’s hands, were the words, “Tom, Beloved Son and Brother.” For several minutes, Tom’s expression was blank. Then he turned to look up at Lynn with his mouth slightly open and his eyes blinded by the light shining in on his spirit, “But I don’t understand. This doesn’t make any sense.”

Lynn smiled, “No, Tom, it doesn’t. But I want you to consider: what would have happened if your sister had not died? What if you were the one who died that day, not her?”

“But I woke up, and they were all gone. I saw it happen—right there in front of me. She was dead. Then I saw this grave up on the hill by the cottonwood we used to play under all the time, and it all made sense. This doesn’t make any sense at all.”

Source

“Here,” said Lynn, “look at this.” She pulled a small, silver locket from beneath her blouse and handed it to him. Tom held it in his left hand. He looked intently and brought the forefinger of his right hand up to touch it.

“But this was June’s. This was hers.”

“And now it belongs to me.”

Tom looked up at Lynn with new eyes, “You’re my…niece? But if you knew this, then why didn’t you tell me?”

“I didn’t know, Tom. Not at first. My mother never told me she had a brother. You see, she, too, was tortured with guilt; I never knew why. I’m convinced now that she blamed herself for your death. After all, if she had not been hiding in the barn, you never would have dropped the match. I really had no idea what I would find here. I certainly didn’t expect to find a fifty-year-old ghost.”

“So, what does this mean?” asked Tom, “What happens now?”

“I don’t know,” replied Lynn.

As Tom turned his attention back to the locket, he began to change; the age began to melt away from his hands, the wall around his spirit began to crumble, and his grief began to fade. He closed his hand around the locket, squeezed it, and returned it to Lynn. He stared at his hand, turning it over in amazement as the self-imposed illusion fell away.

Source

Finally, he stood and looked at Lynn through the clean, clear eyes of a nine-year-old boy. He turned to look back at the house and was shocked by what he saw there. The well-kept, whitewashed farmhouse was gone. The forty years that he lost in that moment were regained by the old farmhouse; the doors were cracked, the windows were broken, the walls were coming apart, and some of the roof had caved in. He looked to the patch of ground he had worked for the past forty years and found it indistinguishable from the land that surrounded it. It was, in fact, as if he did not exist. He smiled and spoke in the high-pitched tenor of a young boy’s voice, “But this means that I didn’t do it.” He turned his youthful eyes to Lynn. “I didn’t kill my sister.” A smile. An open, free, and joyful smile.

“No. You didn’t,” was Lynn’s simple reply.

He looked out across the horizon at something that Lynn could not see. His face bloomed with the joy of recognition.

“Go, Tom. She has been waiting for you. They have all been waiting for you, and it’s time that this wound was healed for everyone.”

Tom turned to Lynn for one last time as fresh tears ran down his face. He smiled at her, as only a child can, and gave her a wild, passionate hug. Lynn smiled as she watched him shimmer and fade into the arms of his sister, releasing a heavy burden from her own heart as he went. “Thank you,” she said.

Source

As Lynn walked out from under the shade of the cottonwood tree, eager to return to her own family so many miles away, she thought she heard Tom’s voice whisper, “Thank you.” And his voice was the breath of the soft warm breeze of spring, finally come to revive the land once more.